Beyond Vengeance

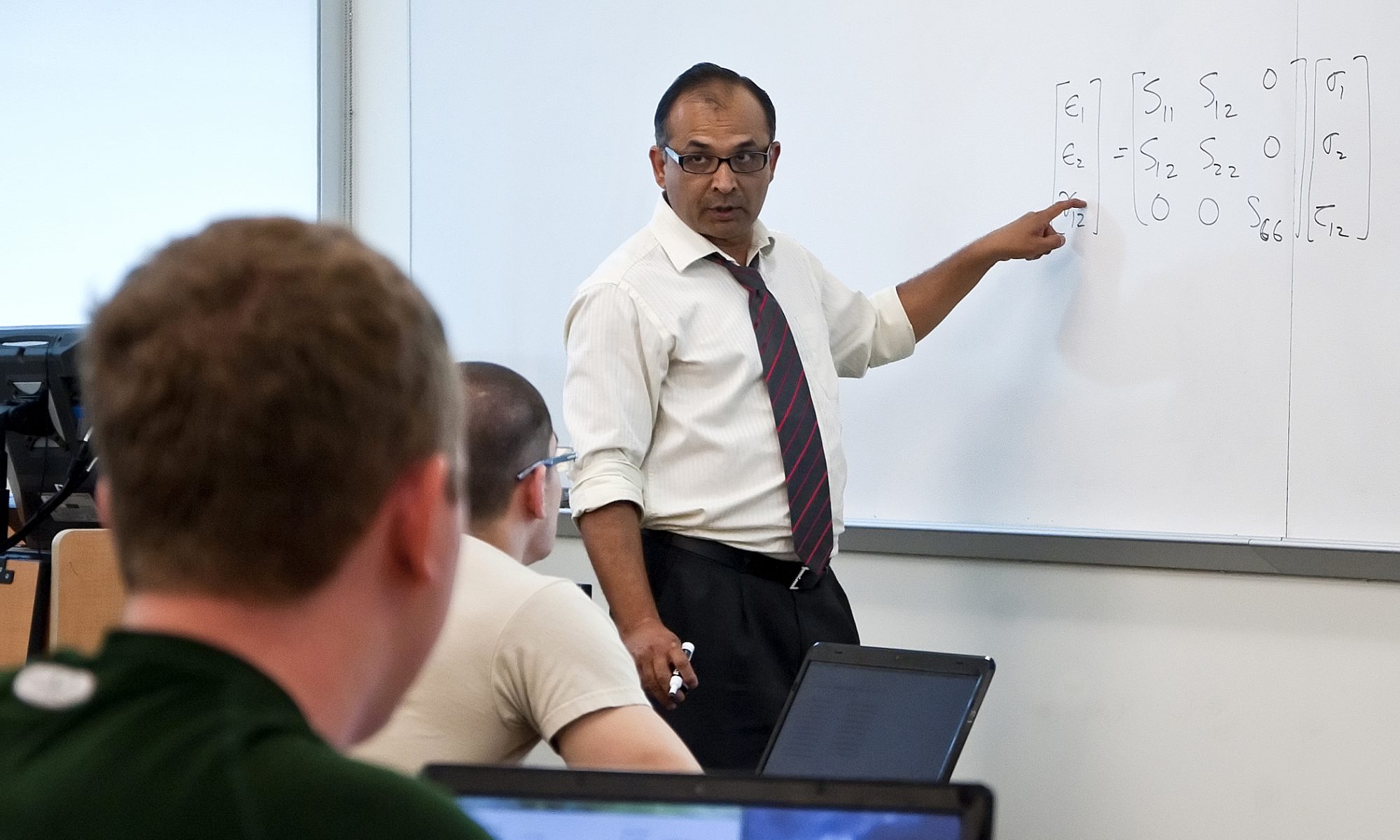

AUTAR KAW

Religion Column

Tribune Correspondent

The Tampa Tribune

December 5, 1998

On August 25, 1990, at 1:05 A.M. when the telephone rang, we let it ring as we now knew better who would possibly be on the other side. Whenever we picked the phone during the late hours of the night, callers would either enthusiastically or with lonely desperation ask, “Is this Paradise?” Our phone number was so close to this place of business of carnal pleasure that we thought several times of asking GTE to give us a new telephone number.

But, this time, the phone rang several times but they would not hang up. “Might as well pick it up?” said my spouse. I picked the phone, and in a thick Indian accent, the voice on the other side said, “May I speak to Mr. Kaw?” I replied, “Yes, this is Mr. Kaw.” The voice on the other end confirmed my identity three times. Suddenly, I remembered a few of my friends who had gone through this drill of confirmation of identity and before I could brace myself, the voice from across the seas in India confirmed my worst fear, “I am a spokesperson from the Home Ministry of India. I have some serious news for you. Mr. Radha Krishen Kaw is no more. He was murdered yesterday in Srinagar, Kashmir at gunpoint by unknown militants.”

Approximately at 10 A.M. on August 24, 1990, two of my father’s friends asked him to meet them outside of a school in which he was teaching. They pretended that they had something important to discuss. When he came out, at gunpoint they took him to a deserted alley and shot him point blank in the head. My father’s body lay on the ground and onlookers and the police provided him no help till he took his last breath.

You must be wondering what had he done to deserve to die in hands of his own “friends”? His crime – being a Hindu; not for practicing Hinduism but for being a Hindu. (Before any reader throws his arms up in the air about the bluntness of this statement, I want to say that I am telling the story of my father and how my faith healed me. I am not interested in making any political statement in my article. The pain is the same when a loved one is murdered, no matter what your racial, religious, national and economic background is. People of all religions have been perpetrators and victims of religious hate crimes. Many innocent Muslims, some of them my friends, have died in the hand of militants in Kashmir.)

My home state, Kashmir has been a hot spot since 1947. However, the turmoil used to be limited to skirmishes on the borders of India and Pakistan and Indo-Pak wars. Closer to home there were several serious episodes of civil unrest but they were limited to burning of buses and businesses, stone throwing and riots. However, since 1989, the rules of unrest had changed to civilians being armed with AK-47’s, grenades and rockets. The boldness of militants was ever increasing with murders of prominent political and social members of the society.

This unprecedented unrest in Kashmir launched several requests to my father to leave the state like all my relatives and friends had done in early 1990. My father simply said, “I was born here! My parents and grandparents were born here! This is where I have lived my entire life of 58 years. Why should I leave?” I could not question that reason but I still tried to convince him that he should leave for the sake of my mother, sister, and niece. To this, he said, “They can leave but I am staying! I will arrange a place for them to stay but this is my place to live!”

Although my father was idealistic in many ways, I think in his heart, he was confident and calm that no harm will come to our family. He had close friends across ethnicities and religions in the city and he had selflessly devoted most of his professional life teaching students from every walk of life. He had not just touched his students one at a time but transformed their lives through the gift of being a good teacher. He felt protected and insulated from the ethnic turmoil. But, they proved him wrong on the fateful morning of August 24, 1990.

Was religion now going to let the ones left behind continue to keep faith in God and let us grieve my father’s departure from this earth? Alternatively, were we going to ask God repeatedly why He took my father away? These questions were overpowering and with such dichotomy that it would take nothing else but an unusual strength of faith, conviction, and principles to deal with them.

After much pondering but not for too long, the answers were nowhere but in my faith itself. Hinduism believes in life after death. The body dies but the soul lives forever. Those militants did take my father’s body but they could not touch his soul. This belief brings utmost peace to my mind as it allows me not only to go beyond the thoughts of vengeance, retaliation, and hatred, but to the thoughts that one day when people realize the futility of their bad thoughts and actions, there will be peace among all God’s children.

Hinduism also believes in the Law of Karma. God weighs all our actions and thoughts, good and bad, in divine justice. Then God reincarnates us based on these actions. When a person has achieved the highest Karmic level, good in thoughts and actions through service to other humans, he achieves Salvation and oneness with the infinite soul – God. However, the holy book of Hindus, Bhagavad Gita, categorically states that those who surrender their personal wills to that of Almighty have no Karmic debt and will merge with God in salvation.

But, only a few of us have the capacity to surrender our personal will because man is driven by his ego and it makes such surrender difficult. Therefore, the recourse for the rest of us to achieve salvation is to make wise choices through the free will that God has provided each of us. Salvation is for all; it might just take a few cycles of being reincarnated to reach it.

Hinduism also guided those of us left behind to go through the bereaving process, so that we continue with the precious life God has given us. Hindus consider death as an integral and inevitable part of the life cycle and celebrate it just like a birth or a wedding which are events with a beginning and an end. For ten days after the day of death, the relatives grieve every morning and evening, talking incessantly about the life of the deceased. Although the story stays the same, the bereaved are allowed just to keep on talking.

On the tenth day through the fourteenth day, prayers and gathering are held. Friends and relatives get together for lunch and dinner. Then on the fifteenth and thirtieth day of each month, religious ceremonies and prayers are held for the next six months. After that, they are held every month until the first anniversary of the death.

It has been eight years since my father was murdered. It has been a struggle and spiritual growth for all of us. We think of him often, mostly about the precious time we spent together, the sacrifices he made for his children’s future, the countless hours he spent in transforming one school after another, and the spiritual contentment he had till the last day of his life.

I always remember what my father said to me, “God gave us life to celebrate, both to do and be, to leave the earth a little better than how we found it, and serve our family, friends, and community without expectation of reward. It is because in service you see the likeness of God in yourself and others.”

CITATION: Autar Kaw, “Beyond Vengeance”, Religion Column, The Tampa

Tribune, December 5, 1998, last accessed at http://autarkaw.com/beyond-vengeance/